Popular philosopher Alain de Botton (1969) and art historian John Armstrong (1966) have put up post-it notes at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam that describe the therapeutic effects of art. ‘Art is therapy’, according to them, and the museum director has had that slogan put up on the façade in neon lights.

One of my friends on Twitter walked by and gave it the finger.

Photo: @j_postma

He is not the only one who is critical. ‘Why Alain de Botton is a moron’ was a heading in the British magazine The Spectator. The Rijksmuseum should be ‘ashamed of itself’ for confronting its visitors with these pseudo-therapeutic texts by De Botton.

I discovered Alain de Botton in May 2012, when I read his book The Art of Travel while on holiday. It is a rich book in which De Botton, standing on the shoulders of giants such as the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and the versatile Victorian John Ruskin , expains how travelling is not about your destination, but about how you see the world.

Then I read other books by him. He is the kind of writer who stimulates my curiosity and makes me want to read the classic works to which he refers. Few are capable of making philosophy and higher culture accessible in such an intelligent manner as Alain de Botton.

He is also a sentimental man. Nobody – and I mean nobody! – tweets as soppily as De Botton. 'Mental health: having enough safe places in your mind for your thoughts to settle', or: 'Bitterness: anger that forgot where it came from.’ My goodness.

Which is exactly what I thought after one minute at the Rijksmuseum. Standing in the long queue at the cloakroom, I noticed the first post-it:

‘Waiting in the queue has become a feature of the Rijksmuseum experience.’

Quite. That’s what I would say too if I could use the back entrance, Mister Guest Curator. Waiting is bloody annoying, at the Rijksmuseum or anywhere else.

Before handing in my bag at the cloakroom, I quickly retrieved my iPad. The museum offers free tours on smart phones and tablets. Accompanied by some rousing music, a voice starts reciting De Botton’s texts in Dutch. ‘We want art to make your life a little lighter. This is an opportunity to experience the therapeutic power of art.’

So it is not just about art, it is about how art affects us. And since we find few things as interesting as ourselves, this is an excellent starting point for a tour. Quite amazing what that Vermeer did, but what’s in it for me?

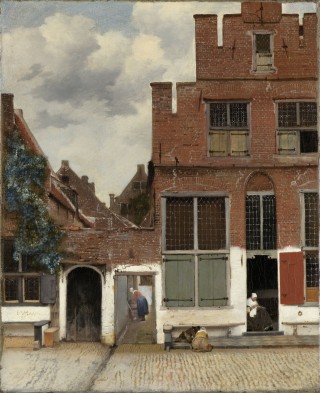

De Botton implies that simply experiencing the beauty of Vermeer’s Straatje (1658) is not good enough. He also wants us to regard the painting as an ode to ‘the Dutch contribution to the universal concept of happiness’, namely ‘that it suffices to carry out the modest tasks expected of us all’. Such as thoughtfully mending our clothes or sweeping the backyard.

View of Houses in Delft, Known as ‘The Little Street’, Johannes Vermeer, c. 1658. Image courtesy of Rijksmuseum

I had never looked at it this way. Actually, all I had done so far was gape at it. So, we move beyond gaping, with De Botton. For instance with The Night Watch. Yes, it is impressive. The most important painting of the Netherlands, I agree. I’ve looked at it many times, overcome with awe.

But it wasn’t until I saw it through De Botton’s eyes that I noticed the irony. ‘You are standing in a crowd and you’re looking at a painting of a crowd. But there is a difference. Your crowd is anonymous and nothing good can come of it. You would love to be alone here. Whereas the camaraderie in the painting brings light to a dark and rainy day.’ Quite a surprising observation, and one that enriched my visit.

The Explosion of the Spanish Flagship during the Battle of Gibraltar, Cornelis Claesz. van Wieringen, c. 1621. Image courtesy of Rijksmuseum

Or take The Battle of Gibraltar by Cornelis Claesz. Van Wieringen. De Botton seizes upon this work to make a case for actively fighting evil, instead of just palavering and having to suppress one’s own fighting spirit and desire for victory. ‘Goodness must have strength as well.’

While studying this sea battle I heard a tour guide explain to a group of young people how the men on board these ships took a crap. ‘You had to clean your arse with your fingernails.’ Nice and gross, exactly as we think teenagers like it. But they will have forgotten it by tomorrow, whereas De Botton’s plea may be a lifelong inspiration to them. It certainly brought the painting more to life for me.

The contrast between the official information and De Botton’s notes is glaring. Where the museum provides mainly technical and historical data, De Botton invariably addresses your psyche.

River View by Moonlight, Aert van der Neer, c. 1640 - c. 1650. Image courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

With River View by Moonlight (c. 1640-1650) by Aert van der Neer, the official text informs us how with just a few colours the painter created ‘the perfect illusion of a moonlit night’. De Botton, on the other hand, urges us to take a walk along a river when the moon is full, in order to reach a state of ‘heightened awareness’ and realize how odd it is that we are here on Earth at all.

Yes, that last bit is quite sentimental again. Sometimes De Botton gets a little carried away. For instance, with Rembrandt’s The Jewish Bride, which supposedly teaches us to acknowledge that we are indeed beautiful and special enough to be loved.

Pulleez…

Or take a collection of sixteenth-century prints about the role of money, where the post-its only offer woolly texts that amount to ‘you can’t buy happiness’.

Duh.

Alain de Botton squats down in a practical sense

All the same, I did enter the prints cabinet and studied each and every one of them. Normally I wouldn’t, as I am not that interested in prints, but this time curiosity got the better of me. Apparently I am so fascinated with De Botton’s view that I now do take an interest in prints. He is the ‘explicator’ I have often longed for. Someone who squats down in a practical sense to offer the spectator a frame of reference outside of the art world.

This was by far the most inspiring visit I ever made to the Rijksmuseum; besides being amazed, I was also encouraged to reflect on this therapeutic effect.

In light of the success of De Botton’s books, his approach may well help the hundreds of thousands of visitors of the Rijksmuseum in experiencing the artworks. It befits this National Institute’s mission and it is a brilliant move.

Which brings me to my appeal to all those who criticize De Botton’s post-its. Please stop prioritizing your own way of seeing things. Okay, so you can do without his approach, and without any type of guidance for that matter. Just don’t deny it all those people who do need it. They are just post-its and you can ignore them if you like. They are just additions, not definite interpretations.

De Botton’s approach to art may not be to everyone’s taste. So be it. Fortunately, in this day and age it becomes increasingly easy for museums to offer alternative ways of looking at their collections. It is simply a matter of providing an app and letting visitors choose their own perspective. Visitors can focus on the historical facts when looking at The Battle of Gibraltar – ‘this is how they took a crap’ – or on the technical details – ‘note how the idea of triumph is rendered’ – or on the aspect of self-help: ‘stop avoiding conflicts’. Or they can make their own mix (personally, I wouldn’t want to miss the official texts provided by the Rijksmuseum): new technology makes it all possible.

De Botton’s tour strikes me as an excellent first step in a richer experience of the museum. So let’s roll up our sleeves, and not just give it the finger.

The exhibition runs until September 7th 2014

Here’s the opening speech by Alain de Botton

This article was translated from Dutch by Leo Reijnen.