One in nine children in my country grows up in poverty. According to Marc Dullaert, former Ombudsman for Children here in the Netherlands, behind this statistic are children who worry every day about things they should be able to take for granted: Is there enough food in the house? Is the heat on? Are there enough clothes?

It’s a situation that’s clearly undesirable, and not just in the short term. Chances are, these poor children will end up being poor adults.

Is there anything we can do? Yes, there is, as the results of multiple studies have shown. We should be able to ward off this fate if we commit to investing in education and care for the youngest children.

Major bodies such as the OECD, the World Bank, and the European Union advise robust investments in these areas. Yet in the Netherlands we’re not making robust investments – we’re investing halfheartedly, which only yields halfhearted results.

Study 1: High-quality education does help

The 1960s had just begun when the young American school psychologist David P. Weikart wondered why the school performance of children growing up in the poorest neighborhoods of his city of Ypsilanti, Michigan, was so far below that of children growing up in more favorable circumstances.

Because he and a number of colleagues suspected that the explanation for these differences could have to do with experiences in early childhood, he decided to begin an experiment. A group of 58 preschoolers growing up in a disadvantaged environment were offered a well-documented educational program that would last until they reached the age of five.

A good twenty years later he compared this group to a control group of 64 children. What came to light? Follow-up at age 27 revealed that the children who had received this high-quality preschool education at the Perry Preschool:

- had been less likely to drop out of school;

- had completed nearly a year more of schooling (11.9 years vs. 11 years);

- had needed less special education and other support services (in total 3.9 years vs. 5.2 years);

- had been more likely to leave school with a diploma (65% vs. 45% in the control group); and

- had had fewer teen pregnancies.

When this group of children had turned 40, the differences were still evident. At that point:

- their median income was 42% higher than in the control group ($1,856 vs. $1,308); and

- they were 26% less likely to have received government assistance (food stamps and other services) in the previous ten years.

Furthermore, the Perry Preschool children:

- were much less likely to have served time in jail or prison (28% vs. 52%); and

- were much less likely to have been arrested for violent crimes (32% vs. 48%).

Study 2: High-quality childcare and education makes a difference

Comparable research results were obtained in the Abecedarian Project, in which children from disadvantaged families were provided high-quality child care and education five days a week (with permanent, college-educated preschool teachers and small groups).

Return on investment in children from 0 to 5 years of age can be eightfold

It is on the basis of these research findings that the Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman came to the conclusion in 2003 that, for a government investing in its citizens, no age is as worth the investment as children between zero and five years old. Heckman contends that the long-term return on that investment can be as much as eightfold (fewer welfare payments; lower expenditures for social, emotional, and cognitive support; less criminal activity).

Is it all right to make such bold statements on the basis of two studies with relatively small sample sizes? Heckman thinks so. He maintains (among other things) that the study outcomes were so strong that they withstand even the most critical statistical procedures.

Family in slum housing on Kleine Kattenburger Street, Amsterdam, in 1962. Photo by Spaarnestad / Hollandse Hoogte

Investing in development pays off

And there is more to support Heckman’s claim.

After the first outcome assessment of the Perry Preschool and the Abecedarian Project – about twenty years after the research began – brain scientists could explain just why the effects of that very high-quality child care and preschool were so pronounced and lasted so long.

Thanks to a range of new research techniques, they discovered that the way the brain develops is not (as was long thought) completely predetermined at birth, but is highly dependent on the emotional care you receive and the extent to which you are challenged to use your brain.

Studies on brain development in children who grow up in poverty appear to confirm these results. The fact is that, in these children, brain development progresses much less favorably.

That, researchers say, purportedly has to do with the stressful circumstances surrounding these children when they are young. Circumstances which make it harder still for parents to respond with sensitivity to their children.

That this sensitive response really is crucial appears to be brought to the fore in recent research at the Erasmus University and the University of Leiden. There, researchers discovered that even a small difference in the way parents respond to the signals and needs of their young child can be connected to “greater total brain volume” (and that was after correction for parents’ education level).

Although a cause-and-effect relationship is not evident, the researchers do find it a plausible interpretation. They believe it “could be an explanation for the positive results that we find in children of sensitive parents,” as one of the researchers was quoted in an Erasmus University press release.

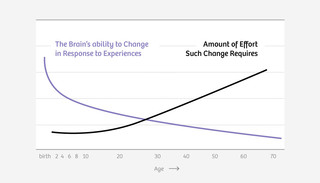

According to brain scientists at the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, it is not impossible for our brain to develop later in life. However, learning does require more effort as we age, as this diagram clearly shows:

Source: Pat Levitt - Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University

In turn, this is consistent with the conclusions that Heckman drew on the basis of the Perry Preschool and Abecedarian Project results: invest generously in the young child, because that is the investment with the highest return for the child and society. It’s no surprise then that Heckman’s conclusion has now been endorsed by the World Bank, the OECD, and the European Commission.

We aren’t really applying these insights

What are we doing with this knowledge? Not nearly enough. And that is worrisome when you consider this: one in every nine children in this country grows up in poverty, and the Child Care and Protection Board identifies poverty as one of the biggest risk factors for child abuse.

Not that the Netherlands doesn’t take into account this knowledge of brain development. For example, children over the age of two who are growing up in disadvantaged families can take part in Early Childhood Education (VVE) programs. And although there is regularly hue and cry about VVE having, no effect whatsoever, the first results from a long-term study by the Kohnstammhuis and Utrecht University – pre-COOL – show that VVE does in fact yield benefits.

However: in an interview, pre-COOL project leader professor Paul Leseman asserts that a great deal of improvement is possible with respect to VVE. Not only should the pedagogical staff administering VVE be better and more regularly coached – “It is truly difficult work” – he also feels that the whole childcare sector (from preschool to daycare) should be professionalized. He believes that this requires:

- well-trained professionals;

- good working conditions;

- a pleasant work atmosphere; and

- solid career opportunities.

“That costs money and does not make for inexpensive daycare,” says Leseman. However, “If you want to contribute to efforts to reduce delays and social disparities, you must be willing to make investments.”

The message that we have to invest more in quality does not only come from Leseman. In its most recent education report, the OECD presents a comparable story. The OECD claims that those who must administer the VVE programs have very little schooling compared to their counterparts in other OECD countries. Moreover, it states that the Netherlands is one of the few countries without a standard curriculum for our youngest children. In other words, we do not yet take development in the first years of life seriously enough.

These findings are especially worrisome for children whose situation at home lacks stability. This is because the VVE these children are provided does not begin until they are two years old. They have, in the two crucial years before it starts, nothing. For children of working parents, daycare can contribute to a solution, but this situation – especially for babies in daycare – is not good enough.

Fortunately, Minister of Social Affairs Lodewijk Asscher has indicated that he wishes to improve early childhood care. Whether that will actually happen, however, remains to be seen. Daycare owners say the plan is not logistically or financially feasible.

Rental in the Jewish quarter, Amsterdam. The municipality rented out this home for one guilder a week to a father with his children. Photo by Spaarnestad / Hollandse Hoogte

The temporary solution: recruit in-home caregivers

In the meantime, can we come up with alternative solutions for these children?

I recently gave a lecture for a group of enthusiastic, well-trained individuals who provide in-home daycare. This is common practice in the Netherlands, where adults provide daycare to a few children in their own homes (or sometimes in the client’s home). The care is much like the care they give their own children – who are sometimes also present. In-home caregivers are registered as such, and the group I was addressing were all part of the agency Zand op de mat.

During our discussion after the lecture, the idea emerged that registered in-home caregivers could provide tremendous support, both for the children growing up in disadvantaged situations and their parents. Unlike in a daycare center, an in-home caregiver has more opportunities to develop a close relationship with a baby, being the only one caring for the child. The caregiver gets to know the baby better and can better respond to the child’s needs.

Research by Leiden University researcher Marleen Groeneveld also points in this direction. In the summary of her doctoral dissertation she writes, “In-home daycare is shown in this study to be more positive than daycare centers.”

Another possible benefit of an in-home caregiver – certainly a pedagogically trained one – is that the caregiver is in a position to support the parents in raising and caring for their baby. The caregiver sees the child on a regular basis.

Of course objections to this plan are conceivable. Not every in-home caregiver would be qualified. And there’s the issue of cost. But until we make the big investments needed in early childhood education and care – until our early childhood programs in this country can earn the approval of Heckman, the OECD, the World Bank, and the European Commission – this seems an interim solution we should consider.

Because child development is happening as we speak. There is no second chance.

—Translated from Dutch by Diane Schaap and Erica Moore

More stories from The Correspondent:

This is what goes wrong inside your head every day

Thanks to our ability to grasp objects and to grasp language – tasks at which our left brain excels – we humans rule the planet. But why do things sometimes go so absurdly wrong? A cautionary tale of what gets skewed within our skulls and what we can do about it.

This is what goes wrong inside your head every day

Thanks to our ability to grasp objects and to grasp language – tasks at which our left brain excels – we humans rule the planet. But why do things sometimes go so absurdly wrong? A cautionary tale of what gets skewed within our skulls and what we can do about it.

Why do the poor make such poor decisions?

Our efforts to combat poverty are often based on a misconception: that the poor must pull themselves up out of the mire. But a revolutionary new theory looks at the cognitive effects of living in poverty. What does that relentless struggle to make ends meet do to people?

Why do the poor make such poor decisions?

Our efforts to combat poverty are often based on a misconception: that the poor must pull themselves up out of the mire. But a revolutionary new theory looks at the cognitive effects of living in poverty. What does that relentless struggle to make ends meet do to people?