What should Dutch people know in order to understand how you feel, being here in this country? There it was, this month’s big question.

“I want people to know that I’m not from some backwards country.” “That I didn’t choose to be here, just for fun.” “That I miss my family so much it hurts.” Three answers, and then in all kinds of permutations. Sometimes the answer came in an explanation or a brief description; sometimes it was packaged in a single, tightly-wound sentence.

As part of the New to the Netherlands initiative, nearly 300 refugees sat down to talk to members of De Correspondent over the last few weeks. Their conversations were guided by a questionnaire made up mostly of multiple choice questions.

At the end of the questionnaire we also asked a few open-ended questions, like the one above.

Here you’ll find a selection of the responses – some are guarded, some of them confrontational, and many come straight from the heart. We have divided them into seven statements – all sentiments that newcomers feel each and every Dutch person should be aware of. We’ve added a brief introduction to each series of answers.

1. That I didn’t choose to be here, just for fun

The vast majority of the newcomers participating in New to the Netherlands are from Syria, have a high school diploma or higher education, and belonged to the middle or upper class in their homeland.

They feel like screaming it at the top of their lungs: They aren’t here for fun or even of their own volition. They feel like they’ve been cast out of paradise. Each of them had a good life in the prosperous nation of Syria, the way it was before the war. Those lives have been ripped away – and the pain of that fact is unceasing.

“We had a good life back in Syria. Here I can only afford second-hand clothes for my children

“In Syria, I had a home, a car, a job, and a fiancée. We had plans for a future together, including children. Because of the war, my fiancée is now dead. I’ve lost my house and my livelihood. I’ve lost everything. Is it even possible to comprehend this kind of loss, if you haven’t been through it yourself?”

“I’m not here of my own free will. The war in my country forced me to come to Europe. I miss my family, my own home, my friends, the whole life I had in Syria. I had to leave everything behind, all those things I studied and worked so hard for for so many years. Here, we have to start from scratch in a foreign country with a foreign culture and a foreign language. I feel completely uprooted.”

“We’re here because it was impossible for us to continue living in Syria. It was too dangerous for us and the children. Members of our family were murdered. The deep sadness of that loss is still with me much of the time. In Syria, we had everything we could wish for. We had a good life. Here I can only afford second-hand clothes for my children, nothing new. Sometimes I feel like a beggar.”

2. That I’m not from some backwards country

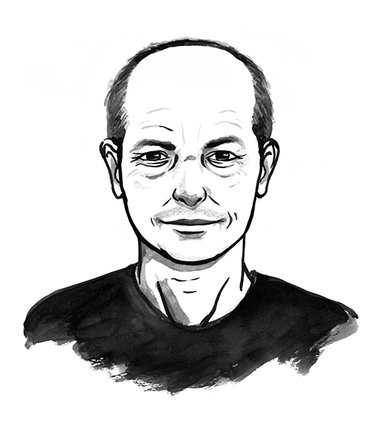

Illustration by Marianne Lock for De Correspondent

As the answers to our questions demonstrate, Syrians are a proud people. Proud of their country and of their culture. They find it humiliating to be treated like backwards members of some stone-age culture. Don’t the Dutch know that Syria is a developed nation with an ancient civilization? And that you can’t just lump together all Muslims and all Arab countries?

“I was asked if I knew how a washing machine works. Apparently, people thought I was used to washing our clothes by hand.”

“Maybe they think we were still living in tents and riding camels.”

“There’s a lot of condescension in how people treat us sometimes. The tendency to interfere with how we raise our children or handle money, for example. Maybe it makes sense that they have to be reassured first, to gain confidence that we won’t get ourselves in any trouble. But by now you would think they’d have figured out that we are responsible adults.

“Dutch people don’t know that the alphabet they use was invented in Syria 3,500 years ago, or that Jews, Christians, and Muslims live in the same neighborhoods and celebrate holidays together.”

“Muslims in Syria are different than the Muslims in Saudi Arabia. I drink alcohol and never pray, for example, while others pray five times a day. In Saudi Arabia, women can’t go out in public without a niqab; they aren’t allowed to drive cars or smoke. In Syria, women can do all those things.”

3. That I’m from a different culture, which can lead to misunderstandings

Whether they’re from Syria, Eritrea, or Iraq, refugees embody an entirely different culture. The consequences can be enormous. Imagine you suddenly found yourself in a country where you weren’t aware of the social mores. A place where the habits, gestures, and behaviors that had always served you well are suddenly no longer understood, but are instead viewed with suspicion and mistrust – just because they are at odds with the prevalent culture.

“People are under no obligation to do their best when it comes to understanding us. We’re the ones who came here. It would be nice, however, if they realized that our traditions and culture are different than those in this country. And that can lead to misunderstandings. Women think it’s ridiculous for me to open the door for them or help them with their coat. They seem to take it as an insult. And Dutch people don’t understand that I don’t like to tell people ‘no’... So sometimes I say ‘yes, maybe’ and then don’t show up. Dutch people think that’s rude – while to me, it would be rude to say ‘no’.”

“People are under no obligation to do their best when it comes to understanding us. We’re the ones who came here

“In Syria, one’s family and neighbors are considered very important. People spontaneously drop in on one another. In the Netherlands, you’re expected make an appointment first. To me, it’s a shame that there’s so little spontaneous contact with Dutch people.”

“It’s so quiet here – everything closes at 6 p.m. and no one’s outside. It’s lonely and boring. Kids just watch TV and play on the computer.”

“As a refugee, you have to learn about Dutch culture. It would be nice if Dutch people would ask about Syrian culture once in a while. Then I could share something with them, too.”

4. That I miss my family

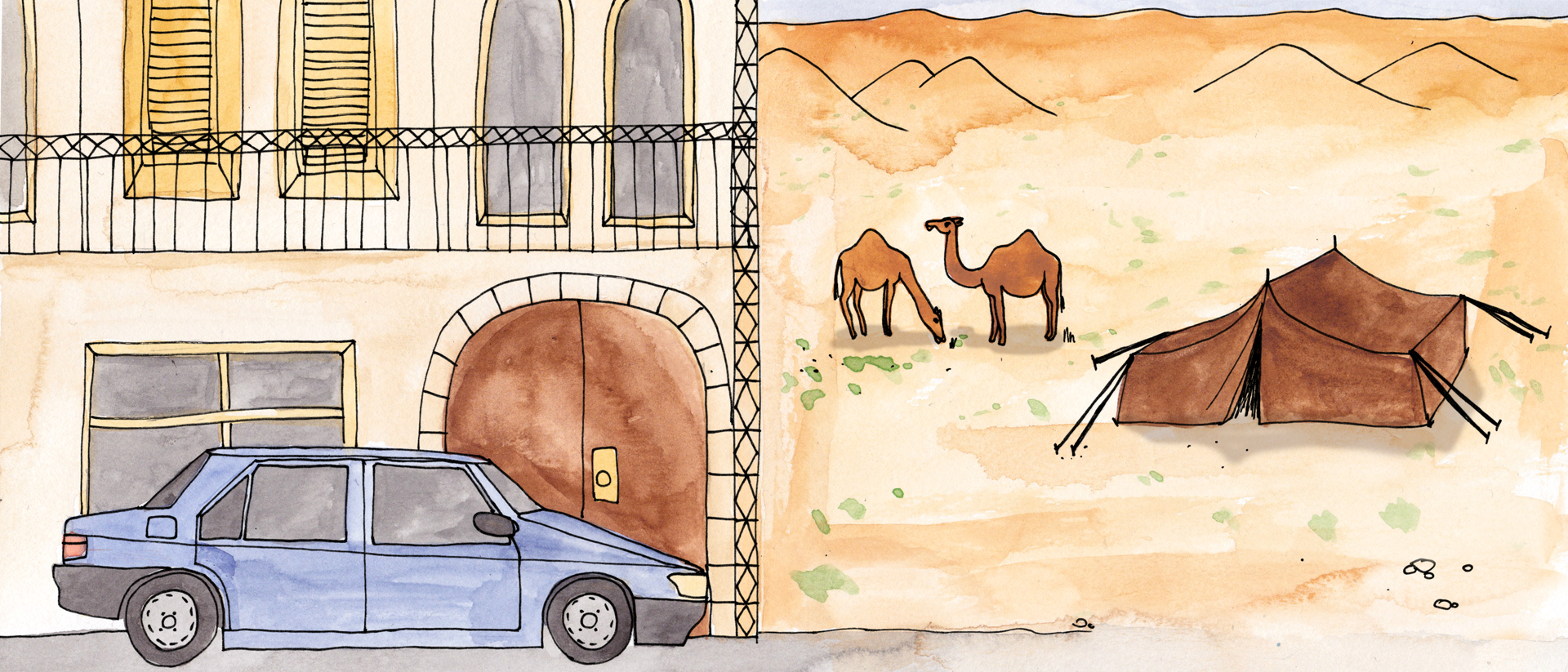

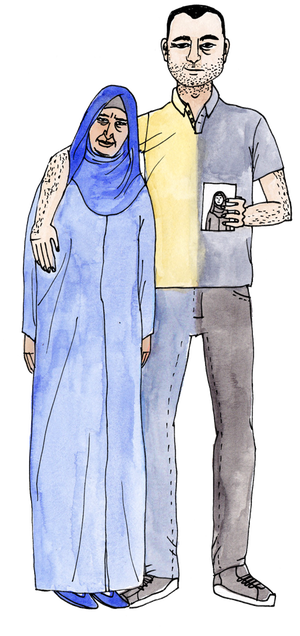

Illustration by Marianne Lock for De Correspondent

Many of the refugees’ complaints sound like cries for help. Newcomers feel like they’ve had a limb severed. Of all the things that torment them, missing their friends and family is the hardest to bear. Back home in their own country, they were surrounded by relatives, neighbors, and friends. Here, many of them are desperately alone. And they are deeply worried about their loved ones elsewhere.

“I miss my wife and children. I’m very worried about them.”

“My wife is still in Ethiopia. That sometimes keeps me up at night, because I’m so worried about her. I can hardly wait until she’s allowed to come to the Netherlands. I’ll feel like the king of the world once she’s here.”

“If my mother were to come here, I would feel better. I’m worried about her and have trouble concentrating as a result.”

“It’s hard to be alone, to have this new life where I don’t know which direction it’s going, what kind of job I’ll be able to get, or whether I can stay here. And meanwhile my parents are still in Aleppo. My brothers are in Algeria and Germany. It’s difficult to live in uncertainty, without knowing what the future holds.”

“I know I’m safe here, but in my mind, I’m still afraid. I am very worried about my parents, who are still in Syria.”

5. That I don’t want to live off welfare

Work, if they only had work. It’s a recurring theme in every conversation. Why is the road to a job so long when you’re a refugee in the Netherlands? Why do you need so many permits to start your own business here? They had jobs before, didn’t they? They have knowledge and experience, right? Or are those things suddenly worthless here?

“Dutch people need to understand that I don’t want to live off welfare benefits: I want to work. And the reason I don’t work is that my Dutch isn’t good enough yet.”

“I’m not here to ask for a handout

“I’m not here to take advantage of the system, and I’m not here as a tourist – I want to contribute to society and work for the money I get.”

“They should know that I didn’t lose everything in Syria. I still have my brain, my knowledge, my experience, and my dreams.”

“I’ve been here for a year and one month now, and I work as a volunteer at a nursing home and with the food bank. Once I speak the language well enough, I plan to get a job here.”

“I’m not here to ask for a handout. I’m here to find safety, to try and make something of my life again.”

6. That I need time to adjust to living here

Of course the refugees are eager to get back on their feet. But something like that doesn’t happen overnight. It takes years.

“Going from the Arabic culture and community to the Netherlands is a major transition. The way people think, and how they live, are both totally different here. We need time to find our footing.”

“Everything is an adjustment for us; we need more time to get our lives back on track

“Government authorities are asking us to simply flip a switch and become Dutch instead of Syrian. But absolutely everything is an adjustment for us. We need more time to get our lives back on track.”

“We have a great deal of life and work experience to offer and would very much like to give something back. But that takes time – and first, we must be given a chance.”

7. That I’m a person too, and I’d like more contact with the Dutch

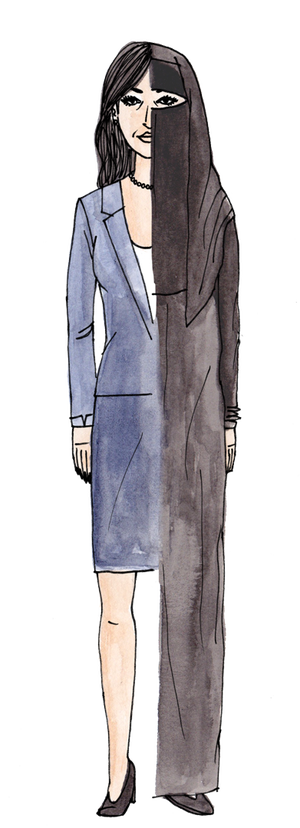

Refugees don’t belong to a different species than you or I. They speak a different language; they eat other kinds of food; they’re used to doing things differently. None of which makes them any less human. Under every headscarf and behind every beard is a person: a unique individual.

Illustration by Marianne Lock for De Correspondent

“I’d like to be seen as a person. I have respect for all faiths, all nationalities, all genders. I’d like others to respect me for the individual I am, with all my abilities.”

“We are people, not monsters. When a girl finds out a particular boy is from Syria, she’ll avoid any real contact with him, because she’s scared. We don’t want people to be afraid of us.”

“I don’t want to be stuck in the pigeonhole marked ‘refugee’. When I tell people I’m from Syria, they immediately assume I need help in some way. I don’t. And when I do need help, I am fully capable of asking for it.”

“I want people to talk to me like a person, not like a refugee. I’m not pitiful.”

“We’re not terrorists – we’re just regular people with regular human needs, like social contact and prospects for the future.”

“More contact would be nice. Dutch people in the village are friendly. They say hello on the street. But that’s as far as the contact goes.”

“If Dutch people avoid all contact with us, they’ll never find out what we think and who we are.”

“We’re not extremists. There’s no reason for Dutch people to fear us. We’re eager for contact with the Dutch, so that we can tell them about who we are.”

—This project is made possible by support from the Dioraphte Foundation. Translated from Dutch by Liz Gorin and Erica Moore

More from De Correspondent: