Here’s how we found the names and addresses of soldiers and secret agents using a simple fitness app

How can a simple running app let you identify military personnel, intelligence operatives, and other users – and even pinpoint their home address? In this piece, we explain step by step how we were able to do it.

In late January, all hell breaks loose when the Strava app publishes a global heatmap displaying all its users’ logged activities. It’s a gorgeous map, visualizing every run and bike ride in glowing color. And it’s public: anyone can view it on the web.

Most of the activity takes place in Western countries. Elsewhere, where there are few Strava users, the map is largely empty. But here and there, sometimes smack dab in the middle of a desert or other inhospitable spot, there’s a burst of rich color.

A few clever investigators soon discover the source of this activity: military bases, some of which are meant to stay hidden. Western military personnel using Strava have unwittingly drawn global attention to themselves and their colleagues.

PHASE 1: A little noodling around

In the Netherlands, Foeke Postma follows the outcry with interest. He’s a diehard runner and a volunteer with the Bellingcat open source intelligence collective. In April, Postma starts using a fitness app made by the Finnish company Polar; he’s curious what data on him the app will collect. Like so many other users, he turns the app on at his front door and doesn’t turn it off until he’s back home.

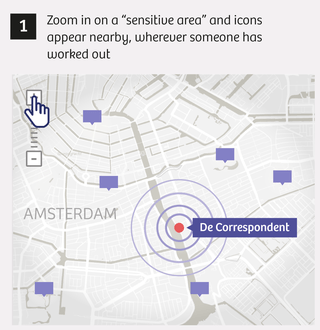

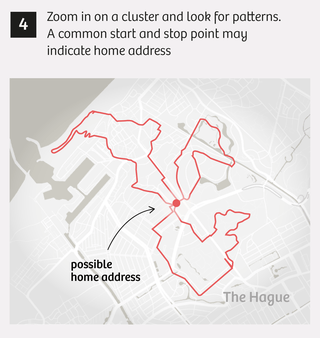

Polar’s map shows him a growing collection of runs near his house. Postma realizes what this means: if he makes his profile public, anyone can see where he lives.

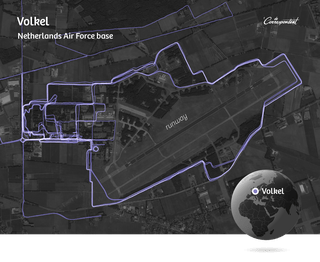

His inner detective comes to life. He scrolls through Polar’s map to find Volkel, a Dutch military base where nuclear weapons are stored. Bam: there’s a run, logged by a jogger who’s used his real name. Postma zooms out and finds additional routes the jogger’s run. The thickest cluster begins and ends at a house in a nearby town.

On LinkedIn, Postma learns that the jogger is a senior officer in the Dutch military. One whose home address he now knows. He repeats the trick at other sensitive locations, with success.

Postma realizes he’s stumbled upon a major security breach. He contacts us and shows us the simple trick he used. We decide to help him, and thus Bellingcat, further pursue the matter.

Before we go on, an important note: in response to our investigation, Polar has disabled its interactive map. It’s no longer possible to reproduce our efforts. Thank goodness.

Here’s how we pinpointed home addresses:

At first we’re all a little blasé about the whole thing. We show a few colleagues the runs near specific sensitive sites, such as an army barracks, and show them how easy it is to track down a runner’s home address. At this point it’s still just a curiosity, an entertaining way to pass a little time.

That changes when we zoom in on the Erbil International Airport in northern Iraq. This airport is home to a military base where several NATO countries – including our country, the Netherlands – are helping Kurdish forces battle the Islamic State terrorist group.

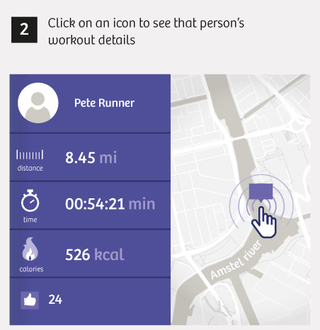

We find four Dutch soldiers, including one we’ll call “Tom.” Given his rapid heart rate and leisurely pace, Tom’s not the fittest soldier at the Erbil base. Nor is he a spring chicken, we see on his Facebook page. The photos he and his wife share there – with all the world – reveal that Tom’s children are in their early twenties. A few minutes later, we’ve tracked down his home address in a small town in the northern Netherlands.

We also stumble across “John.” John’s Facebook page doesn’t mention his mission in Erbil. He’s been careful to keep that information a secret. We do find photos of his child, still a baby, whom he lovingly cradles against his shoulder. And through Polar, we find his house in a working-class neighborhood of a mid-sized Dutch city.

The moment we find Tom’s and John’s home addresses, we realize we’re dealing with information that can endanger people’s lives. What if IS fighters or sympathizers went looking, intent on revenge? What if hackers collected this information and sold it to the highest bidder? It would be just as easy for them to find as it has been for us.

We decide it’s time to get serious. To pretend we’re the kind of people who want to sow fear, to spy on people, to blackmail others into spying. We start systematically searching for targets.

PHASE 2: Systematic searching

Spying and blackmail are potential problems for “Frank,” the senior officer at the Volkel base whom Postma had already found. Nuclear weapons are stored at this base. Someone could use Frank to gather information about base security: by intercepting Frank’s communications, for example, or putting the squeeze on him.

We find Frank’s home address within minutes.We also learn he has at least two daughters. We know where his wife works and what their hobbies are. We have access to photos of every family member.

Frank isn’t the only person logging his workouts at the Volkel base. We find three more. And a home address for every one.

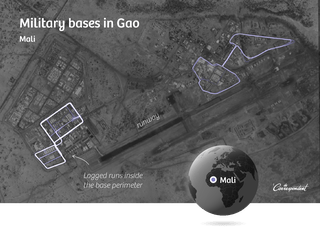

We also find several military personnel stationed at the military base in Gao, Mali. Most of them are Germans. One soldier has parents who live in southern Germany, near the Austrian border, in a charming little house. We also find two Dutch soldiers who have, judging by their workout data, already returned home. In Mali, they never left the base for a single run.

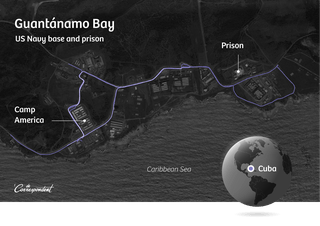

We also examine foreign military bases, including Guantánamo Bay in Cuba, where the infamous American detention camp is located. We see the routes several people run, including ones near the prison. We trace one runner to a home address in a peaceful neighborhood in Dallas, Texas. He’s been arrested for driving while intoxicated, we also discover.

This soldier also leads us to Fort Leonard Wood, a military base in the US state of Missouri. This is where the military guards for places like Guantánamo Bay are trained, we learn from some additional searching. The workouts on Polar’s map could provide valuable clues to locate people who work at other sensitive sites.

Secret services

You would expect intelligence operatives to be untraceable, to have a solid handle on operational security. And in fact, their identities are classified as state secrets in the Netherlands. But Polar’s app makes it a piece of cake to find them.

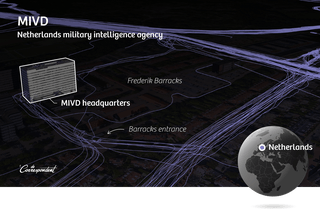

The MIVD, the Dutch military intelligence agency, is headquartered at the Frederik Barracks in The Hague. Polar shows us a smorgasbord of workouts that start and end at that building.

One of the people logging sessions there has listed his real name in the Polar app. We find his LinkedIn account, which says he works for the Dutch defense department. He’s also listed in a publicly accessible online MIVD employee newsletter. Polar’s map shows us that he regularly bikes from the MIVD office to a home address near Rotterdam. The national registry of deeds tells us the exact address.

Another MIVD employee also works out at the Frederik Barracks, but his profile is private. That means we can’t use Polar to find his name. But an oversight in Polar’s app lets us see all his logged activity. The app reveals his unique user number. And you can use that number in searches. The map doesn’t realize we’re looking for a person who’s set his profile to private, and it shows us all his activity.

For example, we see that in January of this year, he repeatedly went running at an air force base in Bamako, Mali. An MIVD employee at an air force base in Mali: sounds more like an operative gathering foreign intelligence for military use than a run-of-the-mill office worker.

We also see him taking runs in the vicinity of a new residential development in the southern Netherlands. At first we have a hard time tracking down his home address, because most of his sessions start in a nearby park. But the possible intelligence operative has also logged a treadmill session. At home. Now we have an exact address. The registry of deeds gives us his name, and that leads us to his LinkedIn profile. He says he’s an analyst at the defense department.

When we walk down his street a few days later, we see his neighbors washing their cars, working in the yard, unloading groceries. At the address we found, we see a man in shorts sitting on his couch watching TV. We instantly recognize him from his LinkedIn photo. We ring his doorbell, and he cautiously opens the door. When we tell him how we found him, he’s flabbergasted. He refuses to say more and refers us to the defense department. And then he shuts the door, as fast as he can.

It’s an uncomfortable confrontation, to be sure. But in truth, over the past few weeks we’ve stood on the digital doorstep of countless people who have very good reason to keep their home address under lock and key.

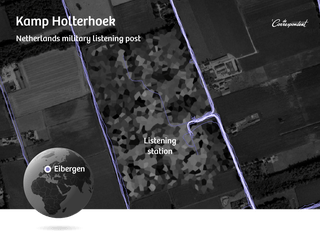

We also search at and around several of the MIVD’s listening posts, such as Kamp Holterhoek in the eastern part of the country. This listening station intercepts radio traffic from all over the world. When two Taliban commanders communicate, Holterhoek personnel are (in theory) listening in. Understandably, this extremely sensitive location has been blurred on Google Maps’ satellite images.

But Polar’s map gives us a way to find out more.

We spot two runners there. One has used his real name in the Polar app. He lives near the city of Arnhem. As we approach his house a few days later, he comes outside and calls a young boy to him, presumably his son. We decide to abort our confrontation. Our point’s already been made: total strangers can come scarily close.

We also find one of his colleagues, whose profile is private. But that’s no problem: we just click on one of his runs, and Polar’s app plays back the whole route for us. It starts at Kamp Holterhoek and ends near a cluster of homes in a nearby town. The registry of deeds tells us the exact address – and who owns it. His Twitter profile says he works for the defense department.

We also search extensively for potential employees of the AIVD, the Dutch civil intelligence agency. We comb the area around the agency’s headquarters, but we come up empty-handed.

Perhaps AIVD employees are more aware than MIVD workers of the risks that fitness apps pose. Or maybe they just don’t like to run.

Not so for several foreign intelligence agencies.

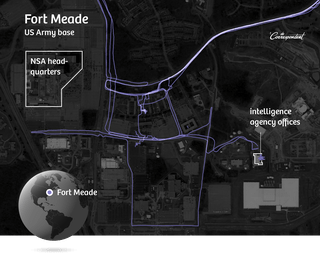

On paper, the NSA is America’s most secretive agency, nicknamed No Such Agency. But at its Fort Meade complex in Maryland, we strike informational gold. We identify multiple people and their home addresses, including:

- a USCYBERCOM officer, responsible for planning cyberspace operations;

- a Belgian military officer, apparently visiting the US, whose tasks include securing the Belgian army’s online networks. We also see him working out at a Secret Service training center;

- several foreign military personnel from Norway and New Zealand;

- a security coordinator for the US Navy;

- the head of medical planning and logistics for the US Air Force;

- and an interpreter.

One Fort Meade runner is harder to track down. His Polar profile is private. Polar’s map leads us to a group of houses where he probably lives, but we can’t pinpoint the exact address and thus we can’t use our registry-of-deeds trick to determine his identity. But there’s another runner in that same neighborhood who also takes regular runs at Fort Meade. She turns out to be a cybercrime response specialist.

We run her through public US databases and discover she’s recently changed her name. Using the new name, we finally locate the house where she and our first runner live. It’s not the address we first found; the couple have recently moved. He’s part of a special intelligence unit.

We also identify people at the FBI’s training center in Quantico, Virginia and the Secret Service training center in Laurel, Maryland. We identify multiple people at Fort Bragg in Fayetteville, North Carolina, where the JSOC special forces – who were responsible for taking out Osama bin Laden, for example – are trained.

We don’t find anything at all near the CIA in Langley, Virginia.

Though Polar’s app seems to be much less popular in Russia, we do find potential intelligence operatives there.

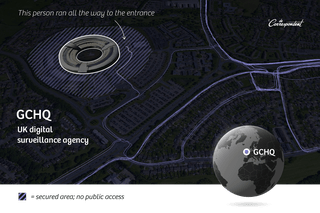

In Moscow, a possible GRU employee makes us work for our data. Polar’s map shows someone running frantic circles around the GRU headquarters.

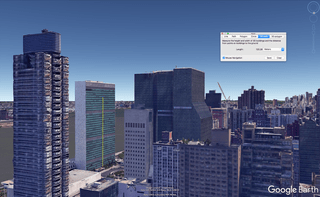

Google Street View clearly shows that the route is in an area that’s closed to the public.

Our Russian runner is hiding behind a private profile, so we don’t have much to go on. When we use our URL query trick to view all his activity, we quickly track him to an apartment building in southern Moscow. Then the trail seems to hit a dead end: the building is enormous, with dozens of floors. Good luck finding anyone there.

But we can zoom in even closer. Polar also displays elevation data – useful for people training to run at altitude. Those data reveal that many of our runner’s sessions start 300 yards above sea level. An online elevation map shows us that the building’s ground floor starts 180 yards up. Then we use Google Earth Pro to measure the building until we reach the value Polar has given us. We end up on the 23rd floor.

We still don’t know much. We know someone’s worked out on the GRU campus; that he possibly lives in southern Moscow, probably around the 23rd floor. But it’s a start. And it demonstrates how easy it is to come within arm’s reach of a total stranger using common sense and a couple of simple tools, even in heavily populated areas.

Another runner is easier to track down. When we examine Polar’s map near the Erbil International Airport, we encounter a Russian who works out there. The Russian consulate is not far away. When we comb through all his sessions, he also turns up in Karachi (Pakistan) and Kabul (Afghanistan), always near Russian consulates and embassies.

This person, who’s registered in Polar under the Russian equivalent of John Smith, also works out at a fitness center in southern Moscow. The Russian search engine Yandex reveals that this location is part of the adjacent complex belonging to the SVR RF. We still haven’t found an address for him. Yet.

On the other hand, one MI6 employee practically hands us his house keys. Polar’s map shows us a session from January of this year, when he ran from the front door of the MI6 building over Vauxhall Bridge to the other side of the Thames and then circled back around via Lambeth Bridge to the north. We type his name into Polar’s search box and bam: a street in west London where many of his runs begin and end. The London telephone book gives us his exact address.

We also find possible employees at MI5 and the GCHQ.

Other sites where we identify people and their home addresses include:

- military bases in France where nuclear weapons are stored;

- NATO’s headquarters in Brussels;

- the DGSE intelligence agency in Paris;

- several other bases, including drone airstrips, in Afghanistan, Chad, Cuba, Djibouti, Germany, Iraq (including the heavily fortified Green Zone in Baghdad), Italy, Mali, Niger, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, the Seychelles, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates.

And finally, we manually explore several other locations whose employees seem unlikely to want their home addresses known. Of these, the most interesting one is the maximum security prison in Vught, where the Netherlands’ most violent criminals are kept.

It doesn’t take us long to find three employees and their nearby homes. This is exactly the kind of data that could earn an unprincipled person money: criminals would be delighted to have such information.

PHASE 3: Big-time data mining

So far, our search for information at sensitive sites has all been done by hand; now we try finding data on a much larger scale. Polar makes this very easy for us.

Here it gets a little more technical.

Suppose you want to find all the workouts logged in Smallville, USA between January 1 and April 1, 2017. You type Smallville into the Polar map search box, the same way you would in Google Maps. You’ll see a menu on the left that lets you enter the time frame you’re interested in. What you don’t see is that this map – which is actually a web application – creates a URL, or web address, that encapsulates your search query.

Polar uses that unique URL to search its user database. The resulting hits are sent to the map page in front of you, which will now display your search results. The map shows a maximum of twenty results, and you can’t search for a time period longer than six months.

Here’s what the map’s request to the database looks like, in a nutshell: the URL for the page that can access the database + GPS coordinates for a geographic region + a “from” date and a “to” date.

We discover that we can create these URLs ourselves, by hand. That means we can directly ask the database for any data we want. We don’t need the map at all. Even better: we can bypass several of the map’s filters and ask to see 400 results at a time, instead of the 20 the map will show us. We can also request all activities since 2014 – a much larger time frame than the six-month maximum the map allows.

Because so many people work out so often in some areas, we have to be smart about our query. So we wrote a program that:

- takes the four corners of a region of the map (in GPS coordinates) as input;

- divides this region into smaller pieces;

- divides the full time span for our search (2014 to the present) into three-month periods;

- and turns each combination of all these into URLs we can fire at the database.

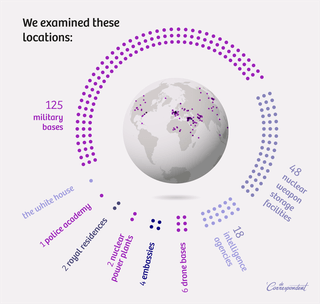

We put together a list of more than two hundred interesting locations: military bases, nuclear facilities, intelligence agency offices, and detention centers. The GPS coordinates for these sites are incredibly easy to find – often using Google Maps, and otherwise through Wikipedia.

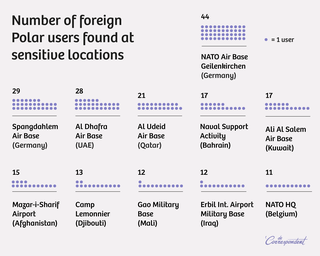

We run all these locations through our program and use the resulting URLs to query Polar’s database. That produces a list of roughly sixty thousand workouts (such as runs and bike rides) that Polar has logged at these locations. Every single one of them reveals the person’s unique user number. Even people whose profiles have been set to private. In total, we find 6,460 users.

Now what?

We can use Polar’s unique user numbers to create new URLs that let us search all these people’s profile pages. Many of them (roughly 90%) have filled in their names and cities. Some of this information will undoubtedly be fake. If someone tells you he’s “Fast Freddie,” you still don’t actually know who he is. But in the spot checks we conduct, the city of residence almost always checks out.

Next, we ask Polar’s database where else these people have worked out – after all, we’ve only located their sessions at sensitive sites. We need to search the entire world for their other runs and bike rides. To our astonishment, Polar lets us simply ask for that information. The database gives us more than 650,000 activities, comprising several gigabytes of data. Polar then – astonishingly – lets us download that information.

Using that complete list of activities, we can accurately determine all the places where these people have worked out. On assignment, at the office, on vacation – and at home. It’s possible to search for places where a user frequently works out and automatically look up the corresponding address using, say, Google Maps. In the end, we decide not to do that. Our point – that it’s dead easy to find a complete stranger’s home address – has been made.

PHASE 4 Other apps

Our final step is to put several comparable apps under the microscope.

The first app is Strava. Last January, the company promised its users and military organizations that it would take steps to better protect this kind of sensitive information.

We quickly determine that not enough has been done. The heatmap with sensitive data is no longer public; you have to be logged in to see it. But it only takes a minute to create an account and gain access to that data.

We also discover something new that wasn’t part of the original outcry: namely, Strava makes it possible to identify not only military bases and other sensitive sites, but individuals and their addresses. We soon identify:

- an inspector general in the US military who runs laps around Guantánamo Bay;

- several American soldiers at Erbil International Airport in northern Iraq;

- several French soldiers at a military base in Gao, Mali;

- and an American analyst who works out at Fort Meade in Maryland, where the NSA is also located.

In short: Strava has not fixed its problems.

The next app we test is Endomondo, from the Under Armour clothing brand. Using this app, we fairly easily find:

- three sergeants and a system administrator at Guantánamo Bay;

- an advisor to the Joint Chiefs of Staff at Fort Meade;

- and two soldiers at Erbil International Airport.

Then we test Runkeeper. It’s harder to determine identities using this app, and much harder to find addresses, but here, too, we find several users in Gao (Mali), at the Volkel military base (Netherlands), and at Guantánamo Bay.

More than just a privacy problem

And so we conclude that this is no run-of-the-mill privacy problem that can be fixed with a couple of software patches and a better FAQ. This is a security problem. Groups of people who should stay invisible to the outside world can be found using consumer technology, and that makes them vulnerable.

People who need to keep themselves and their families out of the public eye in order to stay safe are better off avoiding these kinds of apps, or at least carefully considering the information they divulge.

Their employers must ensure that existing security measures are not undone by this kind of digital sloppiness. And tech companies must realize how sensitive the data they collect, store, and share with the rest of the world really is – and the responsibility that comes with it.

All names in this article have been changed. Translated from Dutch by Grayson Morris and Rufus Kain. The original articles in Dutch can be found here.

All our coverage in English can be found below.